|

|

Did We Sell Each Other Into Slavery?:

A Commentary by Oscar L. Beard, Consultant in African

Studies

24 May 1999

The single most effective White propaganda assertion that continues to make it very difficult

for us to reconstruct the African social systems of mutual trust broken down by U.S. Slavery is the statement, unqualified,

that, "We sold each other into slavery." Most of us have accepted this statement as true at its face value. It implies that

parents sold their children into slavery to Whites, husbands sold their wives, even brothers and sisters selling each other

to the Whites. It continues to perpetuate a particularly sinister effluvium of Black character. But deep down in the Black

gut, somewhere beneath all the barbecue ribs, gin and whitewashed religions, we know that we are not like this.

This

singular short tart claim, that "We sold each other into slavery", has maintained in a state of continual flux our historical

basis for Black-on-Black self love and mutual cooperation at the level of Class. Even if it is true (without further clarification)

that we sold each other into slavery, this should not absolve Whites of their responsibility in our subjugation. We will deal

with Africa if need be.

The period from the beginning of the TransAtlantic African Slave so-called Trade (1500) to

the demarcation of Africa into colonies in the late 1800s is one of the most documented periods in World History. Yet, with

the exception of the renegade African slave raider Tippu Tip of the Congo (Muslim name, Hamed bin Muhammad bin Juna al-Marjebi)

who was collaborating with the White Arabs (also called Red Arabs) there is little documentation of independent African slave

raiding. By independent is meant that there were no credible threats, intoxicants or use of force by Whites to force or deceive

the African into slave raiding or slave trading and that the raider himself was not enslaved to Whites at the time of slave

raiding or "trading". Trade implies human-to-human mutuality without force. This was certainly not the general scenario for

the TransAtlantic so-called Trade in African slaves. Indeed, it was the Portuguese who initiated the European phase of slave

raiding in Africa by attacking a sleeping village in 1444 and carting away the survivors to work for free in Europe.

Even

the case of Tippu Tip may well fall into a category that we might call the consequences of forced cultural assimilation via

White (or Red) Arab Conquest over Africa. Tippu Tip s father was a White (or Red) Arab slave raider, his mother an unmixed

African slave. Tip was born out of violence, the rape of an African woman. It is said that Tip, a "mulatto", was merciless

to Africans.

The first act against Africa by Whites was an unilateral act of war, announced or unannounced. There were

no African Kings or Queens in any of the European countries nor in the U.S. when ships set sail for Africa to capture slaves

for profit. Whites had already decided to raid for slaves. They didn't need our agreement on that. Hence, there was no mutuality

in the original act. The African so-called slave "trade" was a demand-driven market out of Europe and America, not a supply-driven

market out of Africa. We did not seek to sell captives to the Whites as an original act. Hollywood s favorite is showing Blacks

capturing Blacks into slavery, as if this was the only way capture occurred. There are a number of ways in which capture occurred.

Let s dig a little deeper into this issue.

Chancellor Williams, in his classic work, The Destruction of Black Civilization,

explains that after the over land passage of African trade had been cut off at the Nile Delta by the White Arabs in about

1675 B.C. (the Hyksos), the Egyptian/African economy was thrown into a recession. There is even indication of "pre-historic"

aggression upon Africa by White nomadic tribes (the Palermo Stone). As recession set in the African Government began selling

African prisoners of war and criminals on death row to the White Arabs. This culminated as an unfortunate trade, in that,

when the White Arabs attacked, they had the benefit of the knowledge and strength of Africans on their side, as their slaves.

This is a significantly different picture than the propaganda that we sold our immediate family members into slavery to the

Whites.

In reality, slavery is an human institution. Every ethnic group has sold members of the same ethnic group into

slavery. It becomes a kind of racism; that, while all ethnic groups have sold its own ethnic group into slavery, Blacks can't

do it. When Eastern Europeans fight each other it is not called tribalism. Ethnic cleansing is intended to make what is happening

to sound more sanitary. What it really is, is White Tribalism pure and simple.

The fact of African resistance to European

Imperialism and Colonialism is not well known, though it is well documented. Read, for instance, Michael Crowder (ed.), West

African Resistance, Africana Publishing Corporation, New York, 1971. Europeans entered Africa in the mid 1400 s and early

1500 s during a time of socio-political transition. Europeans chose a favorite side to win between African nations at a war

and supplied that side with guns, a superior war instrument. In its victory, the African side with guns rounded up captives

of war who were sold to the Europeans in exchange for more guns or other barter. Whites used these captives in their own slave

raids. These captives often held pre-existing grudges against groups they were ordered to raid, having formerly been sold

into slavery themselves by these same groups as captives in inter-African territorial wars. In investigating our history and

capture, a much more completed picture emerges than simply that we sold each other into slavery.

The Ashanti, who resisted

British Imperialism in a Hundred Years War, sold their African captives of war and criminals to other Europeans, the Portuguese,

Spanish, French, in order to buy guns to maintain their military resistance against British Imperialism (Michael Crowder,

ed., West African Resistance).

Eric A. Walker, in A History of Southern Africa, Longmans, London, 1724, chronicles

the manner in which the Dutch entered South Africa at the Cape of Good Hope. Van Riebeeck anchored at the Cape with his ships

in 1652 during a time that the indigenous Khoi Khoi or Khoisan (derogatorily called Hottentots) were away hunting. The fact

of their absence is the basis of the White "claim" to the land. But there had been a previous encounter with the Khoi Khoi

at the Cape in 1510 with the Portuguese Ship Almeida. States Eric A. Walker, "Affonso de Albuquerque was a conscious imperialist

whose aim was to found self-sufficing colonies and extend Portuguese authority in the East&He landed in Table Bay, and

as it is always the character of the Portuguese to endeavor to rob the poor natives of the country, a quarrel arose with the

Hottentots, who slew him and many of his companions as they struggled towards their boats through the heavy sand of Salt River

beach." (Ibid. p. 17). Bartholomew Diaz had experienced similar difficulties with the indigenous Xhosa of South Africa in

1487, on his way to "discovering" a "new" trade route to the East. The conflict ensued over a Xhosa disagreement over the

price Diaz wanted to pay for their cattle. The Xhosa had initially come out meet the Whites, playing their flutes and performing

traditional dance.

In 1652, knowing that the indigenous South Africans were no pushovers, Van Riebeeck didn't waste

any time. As soon as the Khoi Khoi returned from hunting, Van Riebeeck accused them of stealing Dutch cattle. Simply over

that assertion, war broke out, and the superior arms of the Dutch won. South African Historian J. Congress Mbata best explains

this dynamic in his lectures, available at the Cornell University Africana Studies Department. Mbata provides three steps:

1) provocation by the Whites, 2) warfare and, 3) the success of a superior war machinery.

There are several instances

in which Cecil Rhodes, towards the end of the 19th Century, simply demonstrated the superiority of the Maxim Machine Gun by

mowing down a corn field in a matter of minutes. Upon such demonstrations the King and Queen of the village, after consulting

the elders, signed over their land to the Whites. These scenarios are quite different from the Hollywood version, and well

documented.

It has been important to present the matters above to dispel the notion of an African slave trade that

involved mutuality as a generalized dynamic on the part of Africans. If we can accept the documented facts of our history

above and beyond propaganda, we can begin to heal. We can begin to love one another again and go on to regain our liberties

on Earth.

Respectfully,

Oscar L. Beard, B.A., RPCV

Consultant in African Studies

P.O. Box 5208

Atlanta,

Georgia 31107

AN ARGUMENT FOR THE PAYMENT TO DECENDANTS OF AFRICAN SLAVES:

By Joseph S. Spence, Sr.

Have Comments to share?

Discuss these issues and more with other people.

[Join

the Conversation]

In the past Europeans with ill will almost entirely stripped and raped Africa of its most valuable

resources: gold, ivory, diamonds and its people. The raping of Africa came in the form of disguises by those malevolent Europeans

claiming that they were there to help the African nation. The resulting impact of the disguised "help" was the transportation

of approximately fourteen million Africans from their continent as captives to the West into slavery. Since then many abolitionists

have fought for the ending of slavery. The overt sign of the shackles are gone; however, the covert aspect of slavery still

remains. The prevailing question that springs from the slave experience is that of reparations being paid to the descendants

of slavery. As a result of the brutality, demoralization, genocide and other negative actions inflicted upon Africans because

of the slave trade, including a devastating impact beyond the initial enslavement, we will see that reparations should be

paid to the descendants of slavery.

Europeans of ill will went to Africa with the hidden intent of stripping and raping

the country of its most valuable resources -its young people. Words of untruth were told to Africans. Promises were made with

no intent to be kept. Deception was implemented to trick Africans into a trap of oppression. The hidden plans of the malicious

Europeans were to capture and transport Africans as slaves to be sold in the West. The resulting impact is the kidnapping,

beating, and forced taking of approximately 14,000,000 Africans and their descendants, and enslaving them in the United States

from 1619 to 1865 (Conyers 1).

Africans and their descendants have suffered in the United States as a result of the

slavery imposed upon their ancestors and elders. African-Americans today are still suffering from the "remnants of the badge

of slavery." This came as a result of their ancestors and elders being stolen from their homeland, Africa, and being forced

to work without compensation in a land foreign to them. Their slave owners and their descendants benefited from the fruits

of the African enslavement. On the opposite hand, Africans had their culture, heritage, family, language and religion stripped

from them. The self-identity and self-worth of the proud African people were destroyed by repression and hatred (Conyers 1).

African

women were raped and forcefully seduced into sexual activities for the production of children into slavery. African men who

resisted being sold as slaves and sought freedom from captivity were hunted down, captured, whipped and killed at times. African

boys and girls were sold into slavery for a little or nothing as chattel for their so-called masters. Many slave owners became

wealthy as a result of slave labor from Africans working in fields, farms, barns, and the like, and have refused to pay for

the wealth produced by African slaves. Why should those who profited from such outrageous actions continue to reap the benefits?

Why should those who reaped wealth resulting from such unconscionably inflicted woe upon Africans continue to live the high

life while the descendants of slaves continue to suffer from covert slavery? Granting reparations is a just, fair and equitable

action to take as a corrective measure to alleviate the physical, mental and social wrongs inflicted upon Africans and their

descendants by those who profited from such injustices.

Those who continue to benefit from the spoils of slavery, and

refuse to make things right, have raised some objections to reparations. For example, some have argued that all the slaves

are dead, and the slave masters are also dead; therefore, it is not a good idea to pay reparations to the present generations

because they were not slaves (Carroll 2). This argument is flawed and illogical because reparations over the years were paid

to many within our legal system. For instance, the families of individuals who have died as a result of medical malpractice

by a physician are entitled to just and fair compensation for past and future pain and suffering, loss of consortium for not

experiencing the love and affection of a loved one, loss of income, and other benefits one would classify as reparations.

Furthermore, a precedent on reparations was established when Japanese-Americans were paid reparations for the pain they experienced

in World War II interment camps in the United States (1). Such interment does not compare to the captivity of Africans who

suffered gross injustices from the actions of imposed slavery.

The Jews were also paid reparations as a result of their

imprisonment in concentration camps and their indentured servitude to the Germans. The injustices experienced by the Jews

do not compare in any way, shape, or form to the oppressions and degradation suffered by Africans at the hands of Europeans

and Americans during and after slavery. Those in opposition to the payments of reparations have argued that Americans did

not make such payments; neither was the Jew enslaved by America. Upon examination, negative arguments of this nature are senseless.

For instance, in December 1999, officials from Germany, Eastern Europe and the United States signed a historic agreement to

pay $5 billion in reparations to Nazi slave laborers and their families (Love

1). The Unites States was intimately

involved in the Jewish reparations process. Ask yourself, is it right for America to help those in foreign countries obtain

reparations, while in the same breath it refuses to help African descendants on its own shores here at home who have suffered

greater fates?

U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who discovered late in life that she is of Jewish descent,

spoke on the reparations event. She classified the agreement as the first serious attempt to compensate "those whose labor

was stolen or coerced during a time of outrage and shame." She also states, "it is critical to completing the unfinished business

of the old century before entering the new." America in this instance pressured the Swiss and German nations to correct the

sins of their past (Love 1). Isn't this the perfect example of Washington making amends for past wrongs to others? Was this

accomplishment made possible because the Jews who suffered were not Africans and had a greater political lobby and wealth?

Who will convince America with the truth to pay reparations to African descendants? Or is America so set on not paying reparations

that it turns a blind eye to its own internal problems while policing the world?

There is a feeling among many that

before any consideration of reparations is made, America must first apologize to African-Americans for the oppression inflicted

upon them as a result of slavery. Some African-Americans state that they deserve more respect and will accept respectful treatment

as reparation instead of monetary payments. Others state that they would rather have monetary payments as reparation instead

of an apology or a statement of respect, since such actions do not put food on the table, nor pay the bills. However, there

should be a national recognition of the wrongs fostered upon Black people by the forced captivity and slavery they had to

endure (Jemel 1). Will America come to grips and ever say, "I am sorry for the past wrongs inflicted upon Africans and their

descendants"? Is there so much pride involved here that a simple apology, which will satisfy some, is even too hard to make?

It is obvious that without overcoming the initial stages of denial, reparations may have a long way to go before becoming

a reality for African-Americans unlike other groups that have received reparations.

The issue of how reparations are

to be paid is another common objection by the opponents. It appears that some have decided to negatively argue this issue,

with the hopes that if a decision is not possible the problem may go away. Other opponents believe that they have found a

"soft spot" by which to stop the advancement of the reparation issue. They have decided to use this in their favor to derail

the advancement of reparation payments. Other opponents are under the presumption that if enough disagreement is created between

African-Americans and White-Americans on the payment issue, the initial question of reparations may be dead on arrival. However,

many advocates have proposed viable solutions and recommendations (Jemel 1).

Several attempts have been made in the

past to obtain reparations. States across America have now taken up the issue of reparations with serious debate. Boston University

has even held a debate on reparations. During Boston University's debate, those who argued against reparations were actually

arguing for some form of reparation other than monetary payments. Congressman John Conyers even sponsored a bill on reparations

in 1989 known then as HR 40. During testimony Conyers stated, "I haven't been able to hold a hearing. House Speaker Newt Gingrich

is my biggest stumbling block." Conyers also feels that the opponents to his commission's study on reparations believe that

they are being blamed for something they had nothing to do with (Harper 2). Based on these insights, it is obvious that politics

has played a negative role in reparations. One would speculate that if Newt Gingrich was consulted on reparations over dinner,

and if the Republicans had sponsored the bill, the opposition would not have been that great, and the reparation bill would

probably have been approved.

Just like World War II was the war to end all wars, which did not happen, some Americans

are under the misguided conception that the Emancipation Proclamation officially ended slavery for African-Americans, which

also did not happen. Wars are still being fought and African-Americans are still enslaved. The ratification of the constitutional

amendments following the Civil War did not end the intense discrimination, degradation and depravation suffered by African-Americans

(Conyers 2). The lasting effects of slavery have inflicted low self-esteem, lack of cultural identity and economic dependency

on the descendants of former slaves. However, in the reverse, slavery has provided enormous profits to many White-Americans.

They have enjoyed the benefits of their ancestors' unconscionable acts. Furthermore, they are still acting in an unconscionable

manner by refusing to pay reparations to African-Americans. Additionally, to make matters worst, they are just doling out

menial jobs to African-Americans are still working on a lesser level. As a result, while they go to their mansions and pent

houses, African-Americans have to go elsewhere and live in conditions not as lavish as the descendants who enslaved their

fore parents.

In a recent development to enhance the fight for reparations, The National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations

in America has announced plans to sue the United States government on the reparations issue. One must wonder why such an announcement

is not shown on the major news media such as CNN, MSNBC, or even published in local news media. The organization currently

based in Washington, D.C. is making headway in its preparation. Adjoe Aiyetoro, the group's attorney states, "our team is

convinced that a solidly crafted lawsuit will help us achieve our reparations. Much like our ancestors who fought for 250

years to end chattel slavery, we cannot refuse to demand reparations in every forum because it appears that the government

is unlikely to give it to us or that we do not have agreement as to what form it will take." (2). It appears that accomplishments

by African-Americans in the past came at a price mixed with blood, sweat and tears. It also appears that this may be the path

to take in the future.

In summary, African-Americans have suffered immensely as a result of slavery. Others who have

suffered similar fates have received reparations. Why not African-Americans? The Emancipation Proclamation, Civil War and

the constitutional amendments have not officially solved the issue of racism, discrimination, depravation, and reparations

for African-Americans. Achievements made by African-Americans came with the cost of blood, sweat and tears. The National Coalition

of Blacks for Reparations in America lawsuit may be a potential solution. African-Americans have made great progress by taking

their plea to the courts of law. Tremendous achievements have been made in this arena. Hopefully, such achievements will continue

in the future when a just, fair and equitable court decision is handed down on paying reparations.

REFERENCES

Conyers,

John Rep. "About The Bill." The Proposed Reparations Study Commission. 4 Feb.

2002.

Carroll, Jon. "Reactions to

Reparations." San Francisco Chronicles. (2001). 4 Feb. 2002.

Harper, James. "Bethune Puts The Issue on Trial."

Black Voices About Reparations.

Jemel. "Reparation - A Simple Plan." (1999). 4 Feb. 2002.

Love,

David A. "U.S. Needs to Pay Reparations for Slavery." The Progressive Media Project.

(2000). 4 Feb. 2002.

2005-06-16

Has King Tut been whitewashed?:

US black activists demand King Tut’s

bust be removed from exhibition because its rendition of his face is ‘distortion of reality’.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

LOS ANGELES - US black activists demanded Wednesday that a bust of Tutankhamun be removed from a landmark exhibition of

artefacts from the Egyptian boy king's tomb because the statue portrays him as white.

The bust that activists object

to is a central part of "Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs," the first US exhibition of relics from king Tut's

tomb in nearly 30 years, which opens here Thursday amid Hollywood fanfare.

The face of the legendary pharaoh,

who died around 3,300 years ago at the age of just 19, was reconstructed earlier this year through images collected through

Cat Scans of his mummy, found near Luxor in Egypt in 1922.

But Legrand Clegg, a historian and prosecutor of the

Los Angeles area city of Compton, is demanding that the bust of King Tut be removed from the show because its rendition of

his face is a "distortion of reality."

"They have depicted King Tut as white, but the ancient Egyptians were black

people," he said.

We do not need modern scientists to reconstruct the bust and tell us what to see. Do not deprive

black children of their heritage," Legrand said in an appeal to organisers to remove the likeness from display.

Clegg

said the protest would take the form of a peaceful picket outside the Los Angeles County Museum of Art where the 27-month

three-city tour of the United States is poised to open.

The action comes after Los Angeles city officials declined

to intervene with exhibition organisers to remove the bust.

"There is no evidence that King Tut was white," Clegg

told city officials at a public meeting last week. "Egypt is on the continent of Africa."

Clegg maintains that

the inhabitants of ancient Egypt were descended from the black Nubian people that inhabited that country and neighbouring

Ethiopia.

He said his group would protest as long as there was a "suppression of black history," that he said

was "conspiratorial" and "has to stop."

Organisers of the exhibit billed it as a "blockbuster" display that will

leave its mark on the worlds of archaeology and the American public.

Clegg said his drive was supported in his

quest to have the bust removed by the Compton branch of the powerful National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP).

The show, which boasts 130 funerary objects some of which have rarely or never travelled out of Egypt

before, opens its doors 26 years after the last US display of artefacts from Tutankhamun's tomb ended in 1976.

From"In Defense of Self-Defense":

June 20, 1967

Men were not created in order to

obey laws. Laws are created to obey men. They are established by men and should serve men. The laws and rules which officials

inflict upon poor people prevent them from functioning harmoniously in society. There is no disagreement about this function

of law in any circle the disagreement arises from the question of which men laws are to serve. Such lawmakers ignore the fact

that it is the duty of the poor and unrepresented to construct rules and laws that serve their interests better. Rewriting

unjust laws is a basic human right and fundamental obligation.

Before 1776 America was a British colony. The British

Government had certain laws and rules that the colonized Americans rejected as not being in their best interests. In spite

of the British conviction that Americans had no right to establish their own laws to promote the general welfare of the people

living here in America, the colonized immigrant felt he had no choice but to raise the gun to defend his welfare. Simultaneously

he made certain laws to ensure his protection from external and internal aggressions, from other governments, and his own

agencies. One such form of protection was the Declaration of Independence, which states: ". . . whenever any government becomes

destructive to these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute a new government, laying

its foundations on such principles and organizing its powers in such forms as to them shall seem most likely to effect their

safety and happiness."

Now these same colonized White people, these bondsmen, paupers, and thieves deny the colonized

Black man not only the right to abolish this oppressive system, but to even speak of abolishing it. Having carried this madness

and cruelty to the four corners of the earth, there is now universal rebellion against their continued rule and power. But

as long as the wheels of the imperialistic war machine are turning, there is no country that can defeat this monster of the

West. It is our belief that the Black people in America are the only people who can free the world, loosen the yoke of colonialism,

and destroy the war machine. Black people who are within the machine can cause it to malfunction. They can, because of their

intimacy with the mechanism, destroy the engine that is enslaving the world. America will not be able to fight every Black

country in the world and fight a civil war at the same time. It is militarily impossible to do both of these things at once.

The

slavery of Blacks in this country provides the oil for the machinery of war that America uses to enslave the peoples of the

world. Without this oil the machinery cannot function. We are the driving shaft; we are in such a strategic position in this

machinery that, once we become dislocated, the functioning of the remainder of the machinery breaks down.

Penned up

in the ghettos of America, surrounded by his factories and all the physical components of his economic system, we have been

made into "the wretched of the earth," relegated to the position of spectators while the White racists run their international

con game on the suffering peoples. We have been brainwashed to believe that we are powerless and that there is nothing we

can do for ourselves to bring about a speedy liberation for our people. We have been taught that we must please our oppressors,

that we are only ten percent of the population, and therefore must confine our tactics to categories calculated not to disturb

the

sleep of our tormentors.

The power structure inflicts pain and brutality upon the peoples and then provides

controlled outlets for the pain in ways least likely to upset them, or interfere with the process of exploitation. The people

must repudiate the established channels as tricks and deceitful snares of the exploiting oppressors. The people must oppose

everything the oppressor supports, and support everything that he opposes. If Black people go about their struggle for liberation

in the way that the oppressor dictates and sponsors, then we will have degenerated to the level of groveling flunkies for

the oppressor himself. When the oppressor makes a vicious attack against freedom-fighters because of the way that such freedom-fighters

choose to go about their liberation, then we know we are moving in the direction of our liberation. The racist dog oppressors

have no rights which oppressed Black people are bound to respect. As long as the racist dogs pollute the earth with the evil

of their actions, they do not deserve any respect at all, and the "rules" of their game,

written in the people's blood,

are beneath contempt.

The oppressor must be harassed until his doom. He must have no peace by day or by night. The

slaves have always outnumbered the slavemasters. The power of the oppressor rests upon the submission of the people. When

Black people really unite and rise up in all their splendid millions, they will have the strength to smash injustice. We do

not understand the power in our numbers. We are millions and millions of Black people scattered across the continent and throughout

the Western Hemisphere. There are more Black people in America than the total population of many countries now enjoying full

membership in the United Nations. They have power and their power is based primarily on the fact that they are organized and

united with each other. They are recognized by the powers of the world.

We, with all our numbers, are recognized by

no one. In fact, we do not even recognize our own selves. We are unaware of the potential power latent in our numbers. In

1967, in the midst of a hostile racist nation whose hidden racism is rising to the surface at a phenomenal speed, we are still

so blind to our critical fight for our very survival that we are continuing to function in petty, futile ways. Divided, confused,

fighting among ourselves, we are still in the elementary stage of throwing rocks, sticks, empty wine bottles and beer cans

at racist police who lie in wait for a chance to murder unarmed Black people. The racist police have worked out a system for

suppressing these spontaneous rebellions that flare up from the anger, frustration, and desperation of the masses of Black

people. We can no longer afford the dubious luxury of the terrible casualties wantonly inflicted upon us by the police during

these rebellions.

Black people must now move, from the grass roots up through the perfumed circles of the Black bourgeoisie,

to seize by any means necessary a proportionate share of the power vested and collected in the structure of America. We must

organize and unite to combat by long resistance the brutal force used against us daily. The power structure depends upon the

use of force within retaliation. This is why they have made it a felony to teach guerrilla warfare. This is why they want

the people unarmed.

The racist dog oppressors fear the armed people; they fear most of all Black people armed with

weapons and the ideology of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. An unarmed people are slaves or are subject to slavery

at any given moment. If a government is not afraid of the people it will arm the people against foreign aggression. Black

people are held captive in the midst of their oppressors. There is a world of difference between thirty million unarmed submissive

Black people and thirty million Black people armed with freedom, guns, and the strategic methods of liberation.

When

a mechanic wants to fix a broken-down car engine, he must have the necessary tools to do the job. When the people move for

liberation they must have the basic tool of liberation: the gun. Only with the power of the gun can the Black masses halt

the terror and brutality directed against them by the armed racist power structure; and in one sense only by the power of

the gun can the whole world be transformed into the earthly paradise dreamed of by the people from time immemorial. One successful

practitioner of the art and science of national liberation and self-defense, Brother Mao Tse-tung, put it this way: "We are

advocates of the abolition of war, we do not want war; but war can only be abolished through war, and in order to get rid

of the gun it is necessary to take up the gun."

The blood, sweat, tears and suffering of Black people are the foundations

of the wealth and power of the United States of America. We were forced to build America, and if forced to, we will tear it

down. The immediate result of this destruction will be suffering and bloodshed. But the end result will be the perpetual peace

for all mankind.

Bush to New Orleans:

September 3, 2005

George W. Bush was in New Orleans to deliver a clear

and unmistakable message: Drop Dead. And then, according to various reports, he went off to play golf.

Little in our

history can match his administration's astounding non-response to this excruciating human catastrophe.

Before Katrina,

even Bush's harshest critics might have found non-credible his leaving tens of thousands of American citizens to suffer and

die in utterly gratuitous squalor, disease, hunger and thirst.

Taxpaying American citizens are dying in the heart

of a great city because their government can't be bothered to get them clean water. Or a bed. Or to a hospital.

The

weather has been clear since Katrina passed. Bush commands the world's most advanced armada of land, sea and airborne vehicles.

The resources to save our brothers and sisters are readily available.

But we see our elders, black and white, sitting

confused and in pain, dying of heat and thirst and utter neglect in clear, sunny weather while the President of the United

States babbles aimlessly and the Secretary of State shops for shoes.

We see babies by the dozen dying of dehydration

and hunger where there is no war and no storm, only incompetence and contempt.

Global warming caused this storm. And

there are no secrets about the corruption and stupidity that weakened New Orleans's earthen defenses and opened the floodgates.

The Bush junta slashed funds for levees, let the wetlands be drained, let the developers rape and pillage. It assaulted

those who warned the city would be laid bare to the storms everyone knew would come.

But even from this unelected

gang of thugs and thieves, the horrifying abandonment of New Orleans has taken things to a new level.

Amidst a dire

crisis, American citizens put their trust in the government. They walked into the Superdome. And they were utterly, cynically

abandoned. No food. No water. No emergency electricity. No organized evacuation. No cleaning of the bathrooms. No disinfectants

for the hot, damp, stinking stadium. No provisions for fresh clothing. No medical care for the elderly. No formula for the

babies. No sanitary facilities for pregnant women. No insulin for diabetics. No injections for the sick. No policing. No leadership.

No airlift of doctors, nurses, EMTs, psychologists, medicines….nothing!

Only a big, empty vacuum, the ultimate

symbol of an administration with absolutely nothing in its head or heart.

That the federal government has utterly

failed in these lethal days is universally obvious.

Is it because so many of these people are black and poor? Is it

because Bush has successfully stolen a second term and just doesn't care? Is it because this gouged and battered organization

that was once our government has been so thoroughly exhausted by war and corruption that it cannot or will not manage so basic

a task as bringing the necessities of life to its needlessly dying citizens?

Fox News and macho fools like Haley Barbour,

the corrupt and inept Republican governor of Mississippi, will rant endlessly about a few looters and the shot that may or

may not have been fired at rescue helicopters. We will see endless footage of the African-American family arrested for "stealing"

a car so they could escape and live.

But to hear of dead bodies being stacked outside a professional football stadium

to avoid further stench where ten thousand Americans can't get water, food or sanitary facilities….To see dazed elders

who've just lost their homes or hospital rooms being laid on sidewalks to die…To watch crying children stretched out

on the ground, separated from their parents, dehydrated, overheated, starving….this is too much to bear.

How

utterly can our nation have failed? How totally bankrupt can we be?

As we mourn our most colorful city, the home of

our truest American music, and of so much gorgeous history and culture….we are heartsick and disgraced.

These

global-warmed hurricanes will be coming again and again.

And with this ghastly Bush crew, soul-killing scenes like

these will define our nation.

--

Harvey Wasserman is co-author, with Bob Fitrakis, of How the GOP Stole America's

2004 Election & Is Rigging 2008 (http://www.freepress.org/) , and author of Harvey Wasserman's History of the U.S. (http://www.harveywasserman.com/) .

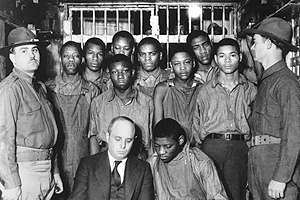

The Scottsboro Boys:

The case of the Scottsboro Boys arose in Alabama during the 1930s, when nine black teenagers, none older than nineteen,

were accused of raping two white women on a train. After a trial which is now regarded as one of the travesties of the American

justice system, the defendants were sentenced to death, despite the fact that one of the women later denied being raped. The

convictions were overturned on appeal, and all of the defendants were all eventually acquitted, paroled, or pardoned, some

after serving years in prison.

The beginnings

The Scottsboro BoysOn March 25, 1931, a skirmish between black

and white men broke out on a Southern Railway freight train after a white man stepped on a black man, Haywood Patterson. All

but one white man, Orville Gilley, were forced off. When the train stopped in Paint Rock, Alabama, the nine blacks were arrested

on charges of assault. Two women dressed in boys clothing, Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, were found hiding on the freight

train as well. They were all taken to Scottsboro, Alabama, the Jackson County seat. The two women agreed to testify against

the boys on a rape charge.

After a lynch mob gathered, the Alabama Governor, Benjamin Meeks Mille, was forced to call

the National Guard to protect the jail. On March 30th, the Scottsboro Boys were indicted by a grand jury and in April all

were convicted and sentenced to death, except one thirteen year old boy who was sentenced to life in prison. In April, the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the International Labor Defense both took up the case, but

the NAACP dropped the case in January, 1932. Despite the fact that a letter surfaced in which Ruby Bates denied that she was

raped, the Alabama Supreme Court affirmed the convictions of seven of the Boys in March, 1932. Samuel Leibowitz, a noted Jewish

attorney from New York who was widely known for winning the vast majority of his criminal cases, defended the boys.

The

U.S. Supreme Court

On November 7, 1932, in Powell v. Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the defendants were denied

the right to counsel, which violated their right to due process under the Fourteenth Amendment. On April 1, 1935, in Norris

v. Alabama, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the exclusion of blacks from the grand jury which issued the indictment

violated the Boys' Fourteenth Amendment rights.

The end of the case

In July, 1937, Clarence Norris was convicted

of rape and sentenced to death, Andy Wright was convicted of rape and sentenced to 99 years, and Charlie Weems was convicted

and sentenced to 75 years in prison. Ozzie Powell pleaded guilty to assaulting the sheriff and was sentenced to 20 years.

In addition, four of the boys, Roy Wright, Eugene Williams, Olen Montgomery and Willie Roberson, were released after all charges

against them were dropped. Later, Alabama Governor Bibb Graves reduced Clarence Norris' death sentence to life in prison.

Norris was later pardoned by the governor. All of the Scottsboro Boys were eventually paroled, freed or pardoned, except for

Haywood Patterson, who was tried and convicted of rape and given the death penalty four times. He escaped north to Detroit.

When he was later arrested by the FBI in the fifties the governor of Michigan did not allow him to be extradited back to Alabama.

He died a free man in the 1960s.

The Haitian Revolution:

1794 - 1804

INTRODUCTION

In August 1791, a massive

slave uprising erupted in the French colony Saint-Domingue, now known as Haiti. The rebellion was ignited by a Vodou service

organized by Boukman, a Vodou houngan (High Priest). Historians stamp this revolt as the most celebrated event that launched

the 13-year revolution which culminated in the independence of Haiti in 1804.

In the 18th century, Saint-Domingue became

France's wealthiest producing colony. The wealth came from a plantation system based on the labor of black slaves, imported

from Africa. Recipients of the wealth were mainly French planters and gens de couleur of African and French descent. The third

and fourth positions of the stratified class system were filled by a small amount of middle class whites (artisans, merchants,

shop keepers) and a lesser number of lower class whites (mechanics, overseers, sailors and soldiers). Ranking last were about

500,000 black slaves, outnumbering all others by about ten to one.

At the time of the slave uprising, the colony was

in a melee with several revolutionary movements brewing simultaneously. The planters were moving toward independence from

France, the free people of color wanted full citizenship, and the slaves wanted freedom. All were largely inspired by the

French Revolution of 1789 with its call for liberty and equality.

One of the most notable leaders of the Haitian Revolution

to emerge was Toussaint L'Ouverture, a former slave. Toussaint organized armies of former slaves which defeated the Spanish

and British forces. By 1801 he conquered Santo Domingo, present-day Dominican Republic, eradicated slavery, and proclaimed

himself as governor-general for life over the whole island.

In 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte dispatched General Leclerc,

along with thousands of troops to arrest Toussaint, reinstate slavery, and restore French rule. Toussaint was deceived into

capture and sent to France, where he perished in prison in 1803. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, one of Toussaint's generals and

a former slave, led the final battle that defeated Napoleon's forces. On January 1, 1804, Dessalines declared the nation independent,

under its indigenous given name of Haiti, thus, making it the first black republic in the world and the first independent

nation in Latin America.

The Haitian Revolution was a remarkable phenomenon, which is of great importance for many

people concerned with revolutionary class struggles, colonialism, black history, Latin American and the Caribbean, particularly

with the country of Haiti. The year 2004 will commemorate the bicentennial celebration of Haiti's Independence. It is hoped

that this pathfinder will be a valuable guide for the anticipated growing number of people who will want to learn about the

Haitian Revolution. It is also hoped that it will serve to honor this heroic struggle in world history.

Resource

Bank Contents

The French Revolution of 1789 not only propelled all of Europe into a war, but also touched off slave

uprisings in the Caribbean. On Saint Domingue, the free people of color began the chain of rebellion when French planters

would not grant them citizenship as decreed by the National Assembly of France in its "Declaration of the Rights of Man."

A

bloody, thirteen-year revolution ensued, a complex web of wars among and between slaves, whites, free people of color, France,

Spain and Britain that would eventually create the first independent black nation in the Western world.

In 1794 France

built upon the "Declaration of the Rights of Man" and officially abolished slavery in its colonies. Toussaint L'Ouverture,

the leader of the Saint Domingue rebellion, abandoned his Spanish allies, joined the forces of the French Republic as a brigadier

general, and turned his troops against Spain.

In 1797 Toussaint was made commander-in-chief of the island by the French

Convention. Following the defeat of the Spanish and British forces, Toussaint began moving toward independence from France.

With Toussaint as its Governor for life, St. Domingue was still technically a French colony, but was acting as an independent

state.

In 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte, who had seized power in France in 1799, sought to restore slavery to the West Indies

through political guile and military force. Toussaint was captured and exiled, but the fighting continued under the leadership

of Jean Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe. On January 1, 1804, Dessalines proclaimed himself ruler of the new nation,

which was called Haiti, a "higher place."

Haitian Revolution:

Haiti--History

Haiti--History--Revolution, 1791-1804

Haiti--Politics

and government--1791-1804

Toussaint L'Ouverture

Famous Characters:

Toussaint Louverture, 1743?-1803

Dessalines,

Jean-Jacques, 1758-1806

Henri Christophe, King of Haiti, 1767-1820

Boyer, Jean Pierre

Leclerc, Charles

Sonthonax,

Leger Felicite, 1763-1813

Petion, Alexandre

Royal African Company:

The Royal African Company was a slaving company set up by the Stuart

family and City of London merchants once the former retook the English throne in 1660. It was led by James, Duke of York,

Charles II's brother.

Originally known as the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa, it was granted a monopoly

over the English slave trade, by its charter issued in 1660. With the help of the army and navy it established trading posts

on the West African coast, and it was responsible for seizing any rival English ships that were transporting slaves.

It

collapsed in 1667 during the war with Holland, and re-emerged in 1672.

In the 1680s it was transporting about 5000 slaves

per year. Many were branded with the letters 'DY', after its chief, the Duke of York, who succeeded his brother on the throne

in 1688, becoming James II.

Between 1672 and 1689 it transported around 90,000-100,000 slaves. Its profits made a major

contribution to the increase in the financial power of those who controlled the City of London.

In 1698, it lost its

monopoly. This was advantageous for merchants in Bristol, even if the Bristolian Edward Colston had already already involved

in the Company. The number of slaves transported on English ships then increased dramatically.

The company continued slaving

until 1731, when it abandoned slaving in favour of trafficking in ivory and gold dust. It was dissolved in 1752, its successor

being the African Company.

The Royal African Company's logo depicted an elephant and castle.

House of Stuart

The

Coat of Arms of Queen Anne, the last British monarch of the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart or Stewart was a Scottish,

and then Great Britain's, Royal House of Breton(British) origin. The House started off ruling Scotland but after the death

of Elizabeth I of England, the last monarch from the House of Tudor, took over the whole of Britain. It was followed by the

House of Hanover. The House began with the hereditary High Stewards of Scotland.

The earliest known member

of the House of Stewart was Flaald I (Flaald the Seneschal), an 11th century Breton noble who was a follower of the Lord of

Dol and Combourg. Flaald and his immediate descendants held the hereditary and honorary post of Dapifer (food bearer) in the

Lord of Dol's household. His grandson Flaald II was a supporter of Henry I of England and made the crucial move from Brittany

to Britain, which was where the future fortunes of the Stewarts lay.

Walter the Steward (died 1177), the grandson of Flaald

II, was born in Shropshire. Along with his brother William, ancestor of the Fitzalan family (the Earls of Arundel), he supported

Empress Matilda during the period known as the Anarchy. Matilda was aided by her uncle, David I of Scotland, and Walter followed

David north in 1141, after Matilda had been usurped by King Stephen. Walter was granted land in Renfrewshire and the position

of Lord High Steward. Malcolm IV made the position hereditary and it was inherited by Walter's son, who took the surname Stewart.

The

Crown of Scotland

The sixth High Steward of Scotland, Walter Stewart (1293-1326), married Majory, daughter of Robert

the Bruce, and also played an important part in the Battle of Bannockburn currying further favour. Their son Robert was heir

to the House of Bruce; he eventually inherited the Scottish throne when his uncle David II of Scotland died childless in 1371.

In

1503, James IV of Scotland attempted to secure peace with England by marrying Henry VII's daughter, Margaret Tudor. The birth

of their son, later James V, brought the House of Stewart into the line of descent of the House of Tudor, and the English

throne. Margaret Tudor later married Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus, and their daughter, Margaret Douglas, was the mother

of Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. In 1565, Darnley married his half-cousin Mary, the daughter of James V. Darnley's father was

Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox, a direct descendant of James II and Mary's heir presumptive, who had changed the spelling

of his surname whilst at the English court. Therefore Darnley was also related to Mary on his father's side, and at the time

of their marriage was himself second in line to the Scottish throne. Because of this connection, Mary's heirs remained part

of the House of Stewart.

White Enslavers Raping Black Women:

A while ago I was watching a talk show and the subject was interracial relationships. At one point, the conversation came

to people who claimed to be pure white or pure Black. The host claimed that no one was of pure ethnicity because there had

been too much race mixing in the past. This brought the conversation to how white slave "masters" raped their Black female

slaves. The white female host made the implication that the only reason the white men raped Black women is because their wives

refused to give them as much sex as they wanted.

This is insulting because it implies that the white men didn't find

the Black women attractive and only wanted them because they couldn't get what they really wanted. The truth is, in that time

period, women had no more rights than Black people. If a white man wanted to rape a white woman, it would have been just as

easy as raping a Black woman. In fact, the only reason a white man had to rape a Black woman is because that is what he preferred.

Black people get insulted every day in media, whether is be on television, radio, newspapers, or the Internet. There

are entire web sites devoted to the degradation of people of African descent, not to mention TV and radio programs. The fact

is evident in the examples provided by news stations covering the Mike Tyson and O. J. Simpson trials. Both people were talked

about as convicted criminals before their trials ever started. Only messages that supported those beliefs were broadcasted.

The

producers of the media do not concern themselves with evidence or lack thereof, because they only have one goal: to fulfill

the need of white America to believe that nonwhite people are worse than them. White Americans feel shame for the wickedness

their people perpetuated and cannot rest until they justify their own wickedness by convincing themselves that the people

they mistreated deserve to be mistreated. This is what they want to believe so this is what their news media delivers to them,

and they believe it without question as to the accuracy of the reports. It is past time that white people stopped twisting

the truth to make themselves feel good about the things they've done.

Website: African American Culture

http://straightblack.com/culture/

Contact African American Culture

http://www.straightblack.com/culture/African-American-Articles/White-Slave-Drivers-Raping-Black-Women.html

The British colonization of America

When America was allegedly discovered and colonized by England, England did

not populate her American colonies with people who were refined and cultured. If you read the history of England, she did

the same thing here that she did in Australia. All the convicts were sent here to this country. The prisons were emptied of

prostitutes, thieves, murderers, whores and many different kinds of freaks. They were sent over here to populate this country.

When those people jump up in your face today, talking about how the Founding Fathers (Matt. 23:9) from England, know that

they were outcasts from its dungeons and prisons. When these thieves and liars arrived here, they proved it. They created

one of the most criminal societies that have ever existed on the Earth since time began.

Excerpted from Our Bondage

http://www.wpunj.edu/~newpol/issue31/chajua31.htm

.........................................................

SLAVERY WAR CASH CROPS MARX REPERATIONS

Slavery quickly became important to southern agriculture. Southern plantations

grew three major crops: (1) tobacco, (2) rice and (3) indigo. Indigo comes from the inner core of a fibrous stalk. Planters

soaked the stalks for at least two weeks to extract a rich blue dye from the pith. The British textile industry prized the

dye and offered a bonus for every pound produced. Most planters hated the smelly unpleasant work with the rotted stalks so

they forced slaves to handle it. In time the indigo trade depended entirely on slave labor.

ANTEBELLUM SLAVERY

The

enslavement of African Americans in what became the United States formally began during the 1630s and l64Os. At that time

colonial courts and legislatures made clear that Africans--unlike white indentured servants--served their masters for life

and that their slave status would be inherited by their children. Slavery in the United States ended in the mid-1860s. Abraham

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 was a masterful propaganda tactic, but in truth, it proclaimed free only

those slaves outside the control of the Federal government--that is, only those in areas still controlled by the Confederacy.

The legal end to slavery in the nation came in December 1865 when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified, it declared: "Neither

slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall

exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Development of American Slavery

The

history of African American slavery in the United States can be divided into two periods: the first coincided with the colonial

years, about 1650 to 1790; the second lasted from American independence through the Civil War, 1790 to 1865. Prior to independence,

slavery existed in all the American colonies and therefore was not an issue of sectional debate. With the arrival of independence,

however, the new Northern states--those of New England along with New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey--came to see slavery

as contradictory to the ideals of the Revolution and instituted programs of gradual emancipation. By 1820 there were only

about 3,000 slaves in the North, almost all of them working on large farms in New Jersey. Slavery could be abolished more

easily in the North because there were far fewer slaves in those states, and they were not a vital part of Northern economies.

There were plenty of free white men to do the sort of labor slaves performed. In fact, the main demand for abolition of slavery

came not from those who found it morally wrong but from white working-class men who did not want slaves as rivals for their

jobs.

Circumstances in the newly formed Southern states were quite different. The African American population, both slave

and free, was much larger. In Virginia and South Carolina in 1790 nearly half of the population was of African descent. (Historians

have traditionally assumed that South Carolina had a black majority population throughout its pre--Civil War history. But

census figures for 1790 to 1810 show that the state possessed a majority of whites.) Other Southern states also had large

black minorities.

Because of their ingrained racial prejudice and ignorance about the sophisticated cultures in Africa

from which many of their slaves came, Southern whites were convinced that free blacks would be savages--a threat to white

survival. So Southerners believed that slavery was necessary as a means of race control.

Of equal importance in the Southern

states was the economic role that slaves played. These states were much more dependent on the agricultural sector of their

economies than were Northern ones. Much of the wealth of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia came from

the cash crops that slaves grew. Indeed, many white Southerners did not believe white men could (or should) do the backbreaking

labor required to produce tobacco, cotton, rice, and indigo, which were the regions chief cash crops.

As a consequence

of these factors, the Southern states were determined to retain slavery after the Revolution. Thus began the fatal division

between "free states" and "slave states" that led to sectionalism and, ultimately, to civil war.

Some historians have proposed

that the evolution of slavery in most New World societies can be divided (roughly, and with some risk of over generalization)

into three stages: developmental, high-profit, and decadent. In the developmental stage, slaves cleared virgin forests for

planting and built the dikes, dams, roads, and buildings necessary for plantations. In the second, high-profit stage, slave

owners earned enormous income from the cash crop they grew for export. In these first two phases, slavery was always very

brutal.

During the developmental phase, slaves worked in unknown, often dangerous territory, beset by disease and sometimes

hostile inhabitants. Clearing land and performing heavy construction jobs without modern machinery was extremely hard labor,

especially in the hot, humid climate of the South.

During the high-profit phase, slaves were driven mercilessly to plant,

cultivate, and harvest the crops for market. A failed crop meant the planter could lose his initial investment in land and

slaves and possibly suffer bankruptcy. A successful crop could earn such high returns that the slaves were often worked beyond

human endurance. Plantation masters argued callously that it was "cheaper to buy than to breed"--it was cheaper to work the

slaves to death and then buy new ones than it was to allow them to live long enough and under sufficiently healthy conditions

that they could bear children to increase their numbers. During this phase, on some of the sugar plantations in Louisiana

and the Caribbean, the life span of a slave from initial purchase to death was only seven years.

The final, decadent phase

of slavery was reached when the land upon which the cash crops were grown had become exhausted--the nutrients in the soil

needed to produce large harvests were depleted. When that happened, the slave regime typically became more relaxed and less

labor-intensive. Plantation owners turned to growing grain crops like wheat, barley, corn, and vegetables. Masters needed

fewer slaves, and those slaves were not forced to work as hard because the cultivation of these crops required less labor.

This

model is useful in analyzing the evolution of Southern slavery between independence and the Civil War. The process, however,

varied considerably from state to state. Those of the upper South--Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia--essentially passed through

the developmental and high-profit stages before American independence. By 1790, Maryland and Virginia planters could no longer

produce the bumper harvests of tobacco that had made them rich in the earlier eighteenth century, because their soil was depleted.

So they turned to less labor-intensive and less profitable crops such as grains, fruits, and vegetables. This in turn meant

they had a surplus of slaves.

One result was that Virginia planters began to free many of their slaves in the decade after

the Revolution. Some did so because they believed in the principles of human liberty. (After all, Virginian slave owners wrote

some of the chief documents defining American freedom like the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and much of

the Bill of Rights.) Others, however, did so for a much more cynical reason. Their surplus slaves had become a burden to house

and feed. In response, they emancipated those who were too old or feeble to be of much use on the plantation. Ironically,

one of the first laws in Virginia restricting the rights of masters to free their slaves was passed for the protection of

the slaves. It denied slave owners the right to free valueless slaves, thus throwing them on public charity for survival.

Many upper South slave owners around 1800 believed that slavery would gradually die Out because there was no longer enough

work for the slaves to do, and without masters to care for them, the ex-slaves would die out as well.

Two initially unrelated

events solved the upper South's problem of a surplus slave population, caused slavery to become entrenched in the Southern

States, and created what we know as the antebellum South. They were the invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney of Connecticut

in 1793 and the closing of the international slave trade in 1808.

The cotton gin is a relatively simple machine. Its horizontally

crossing combs extract tightly entwined seeds from the bolls of short-staple cotton. Prior to the invention of the gin, only

long-staple cotton, which has long soft strands, could be grown for profit. Its soft fibers allowed easy removal of its seeds.

But this strain of cotton grew in America only along the coast and Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia. In contrast,

short-staple cotton could grow in almost any non-mountainous region of the South below Virginia. Before the invention of the

cotton gin, it took a slave many hours to dc-seed a single pound of "lint," or short-staple cotton. With the gin, as many

as one hundred pounds of cotton could be dc-seeded per hour.

The invention of the cotton gin permitted short-staple cotton

to be grown profitably throughout the lower South. Vast new plantations were created from the virgin lands of the territories

that became the states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas. (Louisiana experienced similar growth in

both cotton and sugar agriculture.) In 1810, the South produced 85,000 pounds of cotton; by 1860, it was producing well over

2 billion pounds a year.

There was an equally enormous demand for the cotton these plantations produced. It was so profitable

that by 1860 ten of the richest men in America lived not just in the South but in the Natchez district of Mississippi alone.

In 1810, the cotton crop had been worth $12,495,000; by 1860, it was valued at $248,757,000.

Along with this expansion

in cotton growing came a restriction on the supply of slaves needed to grow it. The transatlantic slave trade was one of the

most savage and inhumane practices in which people of European descent have ever engaged. The writers of the Constitution

had recognized its evil, but to accommodate the demands of slave owners in the lower South, they had agreed to permit the

transatlantic slave trade to continue for twenty years after the Constitution was ratified. Thus, it was not until 1808 that

Congress passed legislation ending the transatlantic trade.

These two circumstances--the discovery of a means of making

the cultivation of short-staple cotton profitable throughout the lower South and territories and the restriction on the supply

of slaves needed to produce it--created the unique antebellum slave system of the South. It made at least some Southerners

very rich and it also made slaves much more valuable. One consequence was that some American slaves were perhaps better treated

than those elsewhere in the New World, not because American slave owners were kinder, but because American slaves were in

short supply and expensive to replace. The price of slaves increased steadily from 1802 to 1860. In 1810, the price of a "prime

field hand" was $900; by 1860, that price had doubled to $1,800.

The Slave System in the Nineteenth Century

Slavery

in the antebellum South was not a monolithic system; its nature varied widely across the region. At one extreme one white

family in thirty owned slaves in Delaware; in contrast, half of all white families in South Carolina did so. Overall, 26 percent

of Southern white families owned slaves.

In 1860, families owning more than fifty slaves numbered less than 10,000; those

owning more than a hundred numbered less than 3,000 in the whole South. The typical Southern slave owner possessed one or

two slaves, and the typical white Southern male owned none. He was an artisan, mechanic, or more frequently, a small farmer.

This reality is vital in understanding why white Southerners went to war to defend slavery in 1861. Most of them did not have

a direct financial investment in the system. Their willingness to fight in its defense was more complicated and subtle than

simple fear of monetary loss. They deeply believed in the Southern way of life, of which slavery was an inextricable part.

They also were convinced that Northern threats to undermine slavery would unleash the pent-up hostilities of 4 million African

American slaves who had been subjugated for centuries.

REGULATING SLAVERY. One half of all Southerners in 1860 were either

slaves themselves or members of slaveholding families. These elite families shaped the mores and political stance of the South,

which reflected their common concerns. Foremost among these were controlling slaves and assuring an adequate supply of slave

labor. The legislatures of the Southern states passed laws designed to protect the masters right to their human chattel. Central

to these laws were "slave codes," which in their way were grudging admissions that slaves were, in fact, human beings, not

simply property like so many cattle or pigs. They attempted to regulate the system so as to minimize the possibility of slave

resistance or rebellion. In all states the codes made it illegal for slaves to read and write, to attend church services without

the presence of a white person, or to testify in court against a white person. Slaves were forbidden to leave their home plantation

without a written pass from their masters. Additional laws tried to secure slavery by restricting the possibility of manumission

(the freeing of ones slaves). Between 1810 and 1860, all Southern states passed laws severely restricting the right of slave

owners to free their slaves, even in a will. Free blacks were dangerous, for they might inspire slaves to rebel. As a consequence,

most Southern states required that any slaves who were freed by their masters leave the state within thirty days.

To enforce

the slave codes, authorities established "slave patrols." These were usually locally organized bands of young white men, both

slave owners and yeomen farmers, who rode about at night checking that slaves were securely in their quarters. Although some

planters felt that the slave patrolmen abused slaves who had been given permission to travel, the slave patrols nevertheless

reinforced the sense of white solidarity between slave owners and those who owned none. They shared a desire to keep the nonwhite

population in check. (These antebellum slave patrols are seen by many historians as antecedents of the Reconstruction era

Ku Klux Klan, which similarly tried to discipline the freed blacks. The Klan helped reinforce white solidarity in a time when

the class lines between ex--slave owners and white yeomen were collapsing because of slavery's end.)

Not long after

Thomas Jefferson wrote the "Declaration of Independence," a free black wrote Jefferson asking if the "all men are created

equal" phrase applied to blacks. Jefferson replied that slavery embarrassed him but he did nothing about it then or during

his presidency. The Quakers spoke out against slavery during the colonial period but they were the only religious movement

to do so. Anglicans worked among the slaves and attempted to Christianize them.

"The discovery of gold and silver in

America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest

and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signaled the

rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief moments of primitive accumulation.

On their heels treads the commercial war of the European nations, with the globe for a theatre.... If money according to Augier,

'comes into the world with a congenital blood-stain on one cheek', capital comes dripping from head to foot from every pore

with blood and dirt."

-Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1

The brutality and viciousness of capitalism is well known to

the oppressed and exploited of this world. Billions of people throughout the world spend their lives incessantly toiling to

enrich the already wealthy, while throughout history any serious attempts to build alternatives to capitalism have been met

with bombings, invasions, and blockades by imperialist nation states. Although the modern day ideologues of the mass media

and of institutions such as the World Bank and IMF never cease to inveigh against scattered acts of violence perpetrated against

their system, they always neglect to mention that the capitalist system they lord over was called into existence and has only

been able to maintain itself by the sustained application of systematic violence. It should come as no surprise that this

capitalist system, which we can only hope is now reaching the era of its final demise, was just as rapacious and vicious in

its youth as it is now. The "rosy dawn" of capitalist production was inaugurated by the process of slavery and genocide in

the western hemisphere, and this "primitive accumulation of capital" resulted in the largest systematic murder of human beings

ever seen. However, the rulers of society have found that naked force is often most economically used in conjunction with

ideologies of domination and control which provide a legitimizing explanation for the oppressive nature of society. Racism

is such a construct and it came into being as a social relation which condoned and secured the initial genocidal processes

of capitalist accumulation--the founding stones of contemporary bourgeois society.

The fact that an African slave

could be purchased for life with the same amount of money that it would cost to buy an indentured servant for 10 years, and

that the African's skin color would function as an instrument of social control by making it easier to track down runaway

slaves in a land where all whites were free wage labourers and all Black people slaves, provided further incentives for this

system of racial classification. In the colonies where there was an insufficient free white population to provide a counterbalance

to potential slave insurgencies, such as on the Caribbean islands, an elaborate hierarchy of racial privilege was built up,

with the lighter skinned "mulattos" admitted to the ranks of free men where they often owned slaves themselves.

Why

Reparations

Reparations are provided as an acknowledgment of responsibility for wrongdoing, and a partial effort to repair

the damage resulting from the wrongdoing. The wrongdoing is slavery, and the oppression associated with it. The theory concerning

reparations is the effects of slavery are still with us today, and a significant factor in the problems African Americans

face in many aspects of their lives.

In order to consider the necessity or morality of reparations for descendants

of slaves, people must first be able to realize slavery can affect people long after the slavery has ended, and slavery can

also benefit descendants of slave drivers long after the slavery has ended. People must also be able to realize slavery and

oppression can exist in forms not as clearly visible as whips, chains, and cotton fields.

This text will explore the

adversity our race suffers due to slavery and associated practices, as well as the lasting effects of the adversity, and how

they relate to reparations.

Depleting Africa's Greatest Resource

Africa's greatest resource is its people. During

slavery, incredible numbers of African men and women were taken from the people they served, protected, and helped to survive.

Slaves were not always captured randomly. People were chosen who would be the most effective slaves. The most physically capable

people were chosen. This process of removing hard workers from Africa served the purpose of providing slave drivers with a

very able work force, but also deprived the worker's families and societies of that work force.

While this wouldn't

necessarily destroy the Black communities, it led to less production than their would have been, which led to less stability,

comfort, and advancement, as well as other things. The additional work force acquired by the slave drivers led to increased

comfort, stability, and advancement for them, and the profits from selling slaves led to increased comfort for the slave sellers.

This led to increased difficulty for the Black race as a whole, which includes Africans in America.

.................................................................................

Related Sound Tracks From 2bans Roots HipHop. All available for FREE to Download from www.2ban.co.uk

Watch out ma Enemies.

Respect.

NewDay Bro.

Whats The Use?

Authority.

Octoroon:

An octoroon or mustee is the offspring of a quadroon and a European parent, having

ancestry that is one-eighth Negroid. This term is considered obsolete and is no longer in general use.

This was part

of a race classification used in the Spanish and French colonies in the New World, and to some extent also used in the Southern

United States in the 19th century. Octoroons were considered "colored" and often subject to slavery in the colonial era, but

sometimes given more privileges than slaves with a greater degree of African ancestry. The child of an octoroon and a white